Our Story

Ever since 1895, Statkraft has developed into Europe's largest supplier of renewable energy and a global player in energy trading. Explore our history through the decades using the buttons below.

Three newly inaugurated wind farms in the O'Higgins Region of Chile with a combined capacity of over 100 MW are the company’s first in the South American country.

Press release: Statkraft inaugurates three wind farms in Chile

Vartdal comes to the role as President and CEO from the position as Executive Vice President Nordics at Statkraft. She succeeds Christian Rynning-Tønnesen who decided to step down after 14 years in the position.

Statkraft inaugurates the company’s largest wind farm outside Europe, the 519 MW Ventos de Santa Eugênia Wind Complex in Bahia, Brazil. The farm will be further developed as a hybrid wind, solar and battery project.

At its peak, the farm employed almost 2,000 workers. The inauguration follows on from the acquisition of two operational wind farms in the state of Rio Grande do Norte the previous year.

Press release: Statkraft inaugurates the company’s largest wind farm outside Europe in Brazil

This year saw Statkraft sign a record-high number of Power Purchase Agreements, including in Spain, Germany, Finland and Norway. Among the companies securing clean, reliable power were Deutsche Bahn, Hydro Energi AS, and Vitesco technologies.

In Scotland, Statkraft agrees to acquire the Loch Ness pumped storage hydro project from Intelligent Land Investments Group. The acquisition adds to Statkraft’s existing pumped storage portfolio in the UK, Germany and Norway, alongside over 350 other hydropower plants including Rheidol in Wales.

The purchase of Enerfin increases Statkraft's installed capacity for wind power in operation and wind and solar power under construction by 1,500 MW.

In addition, the acquisition places Statkraft among the ten largest wind power producers in Spain and Brazil, and sees the company welcome 170 new employees by 2024.

Press release: Statkraft acquires Spanish based renewables business Enerfin from Elecnor Group

Sweden and Statkraft’s renewable growth journey continues as Statkraft acquires two companies in onshore and offshore wind power: Njordr Offshore Wind AB and Svevind Nordic AB.

The acquisition of a wind power portfolio from Breeze Two Energy in Germany and France grows Statkraft’s repowering portfolio with 337 MW and 39 wind farms.

By expanding its portfolio in the countries, Statkraft delivers on its ambition to accelerate its growth rate across wind, solar and battery storage in established markets. The acquisition comes after Statkraft’s purchase of 39 wind farms across Germany and four wind farms in France from Breeze Three Energy in 2021.

Press release: Statkraft strengthens repowering position with second Breeze series wind farm acquisition

Statkraft’s hydropower journey continues with the opening of two hydropower plants in Norway.

Located on two different sides of the country’s Hardanger plateau, Vesle Kjela and Storlia will together produce enough electricity to power 4,000 homes and contribute to the company and Norway’s extensive hydropower fleet.

Press release: Statkraft opens two new hydropower plants

Statkraft invests in the construction of four new solar plants in Cadiz, with an estimated value in the range of EUR 200m.

The plants are co-located in the Cadiz region with a total capacity of 234 MWp and will further build the company’s position in Spain while contributing to its strategic solar ambitions.

Press release: Statkraft accelerates solar investments - four new solar farms in southern Spain

In 2020, the acquisition of Solarcentury, a global solar developer headquartered in London, is completed. Statkraft integrates the Solarcentury team officially in 2021.The move positions Statkraft as one of the leading developers in the European solar market.

Statkraft expands its footprint in Ireland, confirming the acquisition of five fully permitted solar projects with a combined capacity of 275MWp. The expansion is key step in Ireland’s process of Ireland’s decarbonisation, decreasing the country’s dependence on fossil fuels.

Moglicë hydropower plant begins delivering renewable power to the Albanian grid and is expected to generate approximately 450 GWh per year. The milestone is another step on Albania’s journey towards becoming a regional electricity hub.

The final three wind farms at the Fosen development in Åfjord, Norway become operational. The farms in question are Geitfjellet, Kvenndalsfjellet and Harbaksfjellet. Located on the coast in central Norway, Fosen Wind benefits from some of the best conditions for wind power production in Europe.

The wind development at Fosen was contentious. For the Storheia project in particular, a supreme court ruling stated that the concession was in violation of the reindeer herder's human rights. As a result of a mediation process an amicable agreement was signed ensuring continuation of both reindeer husbandry and wind power. The parties agreed that this resolved the human rights issue.

Statkraft unveils Ireland’s first battery project. The hybrid battery-and-wind project in County Kerry combines 11 MW of battery capacity with 23 MW of onshore wind, making it possible to store locally produced wind power.

Press release: Statkraft unveils Ireland’s first battery project

2015 - 2020

Leading the way in the green shift

During this period, Statkraft used its position as Europe's largest producer of renewable power to underline its commitment to a green future. 100 percent of the company's investments went to growth in renewable energy, and the company took a leading role in the green transition.

Statkraft decided to start construction of the Los Lagos hydropower plant in Chile in 2019.

With an increasing demand for renewable energy and several opportunities for developing both hydro, wind and solar, Chile is an attractive market for Statkraft and in line with the strategy of building scale in each market.

The Los Lagos hydropower plant will be located on the Pilmaiquen River, downstream of Statkraft’s operational Rucatayo hydropower plant.

The data centre industry is one of the world's fastest growing power intensive industries and Statkraft is positioning itself as a facilitator of ready-to-construct data centre sites and supplier of renewable energy.

In 2019, Statkraft partnered with Google to develop and prepare a huge site in Skien, Norway.

Statkraft’s strategic ambition to expand its solar business has resulted in the development of solar plants in the Netherlands, Germany and India, route to market solutions in Europe and a R&D project for floating solar plant in Albania.

Floating solar power being tested in the reservoir at Statkraft's hydropower plant in Banjë, Albania.

The Zonnepark Lange Runde was officially inaugurated in February 2018 and was the largest solar park in the Netherlands to date, generating power for approximately 4,000 households. In India, Statkraft inaugurated an on-site solar power project powering a manufacturing plant belonging to SRF Limited in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. At the Dörverden hydropower site, Statkraft officially commissioned a solar park on an adjacent and unused plot of land in November.

In a targeted effort to secure new revenue streams, Statkraft secured several long-term Power Purchasing Agreements (PPAs) with solar developers and industrial customers in Europe. For instance, Statkraft signed PPAs with BayWa r.e. to bring power from the Don Rodrigo solar parks to customers in the Spanish market.

Aiming to advance in solar technology, Statkraft entered into an agreement with Norwegian Ocean Sun AS in 2019 to deliver a floating solar plant on the Banjë reservoir in Albania. The project will demonstrate the viability of the technology based on competence from Norwegian solar PV and maritime industry.

Statkraft started the expansion of its wind power portfolio in a targeted and strategic effort by ramping up its wind development activities.

In 2017, Statkraft completed the Andershaw wind farm in Scotland and expanded its UK onshore wind portfolio through the acquisition of the Irish and UK wind development business of Element Power Group in 2018. The transaction provided Statkraft with a strengthened position in the UK and a large onshore wind development pipeline in Ireland, one of the selected new growth markets for onshore wind. The construction of the Kilathmoy wind farm in south-west Ireland began in 2018.

In addition, the first of the six wind farms in the Fosen development was completed in 2018 with the official opening of Roan wind farm in 2019, Norway's largest wind farm to date. Storheia and Hitra were operational by 2019, while the three final windfarms Geitfjellet, Harbaksfjellet and Kvenndalsfjellet are next in line in 2020. When the Fosen project is complete, it will be Europe’s largest onshore wind power facility.

Statkraft has expanded its wind power activities outside Europe, by acquiring wind projects in Chile and Brazil.

In 2018, Statkraft acquired eight hydropower plants in Brazil, positioning the company for further growth in the Brazilian market. During the same year, the Tidong hydropower construction project in India was acquired.

Tiding River, India

India’s electricity demand is among the fastest growing in the world and one of Statkraft’s core markets for further growth.

Renewables can’t be part of the solution. They must be the solution. In 2018, Statkraft launched its new strategy from 2018 to 2025, Powering a green future, thus paving the way for future growth within renewable energy.

Pumped storage hydropower plant serves as a kind of green battery where water can be pumped back into magazine for later reuse for power generation and regulatory balancing services in the grid.

Replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources is more urgent than ever and the solution to fight climate change. With assets and experience, Statkraft is well positioned to lead the way.

A main priority of the strategy is optimising and maintaining the existing hydropower portfolio in the Nordics. The strategy also sets ambitious growth targets for hydro, wind and solar power in Europe, South America and India. Increasing amounts of intermittent renewable power generation makes the task of ensuring flexibility, managing risk and contributing to efficient markets more important than ever.

Statkraft is also looking to use learnings from decarbonisation and electrification in Norway and Europe to create new, profitable growth opportunities and expand in other markets.

After 15 years of cooperation, Statkraft and Norfund parted ways as Statkraft sold its shares in SN Power and acquired the remaining shares in the holding company for its assets in South America, India and Nepal within hydro, wind and solar power.

The transaction was a result of a strategic decision to build stronger positions in fewer markets.Throughout 2017, Statkraft fully exited offshore wind through the divestment of the wind farms Sheringham Shoal and Dudgeon and the two projects Dogger Bank and Triton Knoll. This significantly improved Statkraft’s investment capacity for further growth in renewable energy.

At this point, electrification of the transport sector was already having a significant impact on the European energy market. A transport sector fuelled by electricity and a growing charging infrastructure created new business opportunities for Statkraft.

In 2016, Statkraft invested in the Norwegian electrical vehicle charging network operator Grønn Kontakt and acquired all shares in the company in 2019. The Norwegian market has the world's highest share of electric vehicles in the car fleet.

To capitalise on its experiences in Norway, Statkraft went on to invest in German EV charging companies eeMobility in 2018 and E-Wald GmbH in 2019.

Charging station from Grønn Kontakt, now Mer.

The increasing share of renewable power generation demands flexible energy solutions. Statkraft actively contributed to the development of new technologies by finding and enabling new solutions for a changing energy market.

Opening of the battery site in Dörverden, Germany.

In 2016, Statkraft put its first multi-megawatt battery into operation at the site of Dörverden hydropower plant in Germany to contribute to the stabilisation of the power grid in the region. The battery was the first of its kind in the grid area and the technology was perfectly suited for quickly balancing fluctuating energy generation from wind and solar power.

Statkraft later entered into agreement with Grid Battery Storage Limited (GBSL), a leading energy storage developer, to provide route to market and optimisation services for their battery storage project.

With one of the world’s largest Virtual Power Plants, Statkraft was ideally positioned to manage flexible assets using its advanced algorithmic trading infrastructure in real time.

Following the 2015 decision by the Norwegian government to increase its dividend, Statkraft decided to scale down its investments and exit the capital-intensive offshore wind projects.

However, Statkraft decided to go ahead with Europe’s largest onshore wind project in Central Norway. The Fosen wind power project is a joint venture between Statkraft, Nordic Wind Power DA and TrønderEnergi. The project includes six wind farms that will gradually come online between 2018 and 2020, starting with Roan wind farm which was officially opened in 2019.

Roan wind farm

An important focus area for Statkraft in 2015 and 2016 was to maximise the long-term value of the company's Nordic hydropower plants.

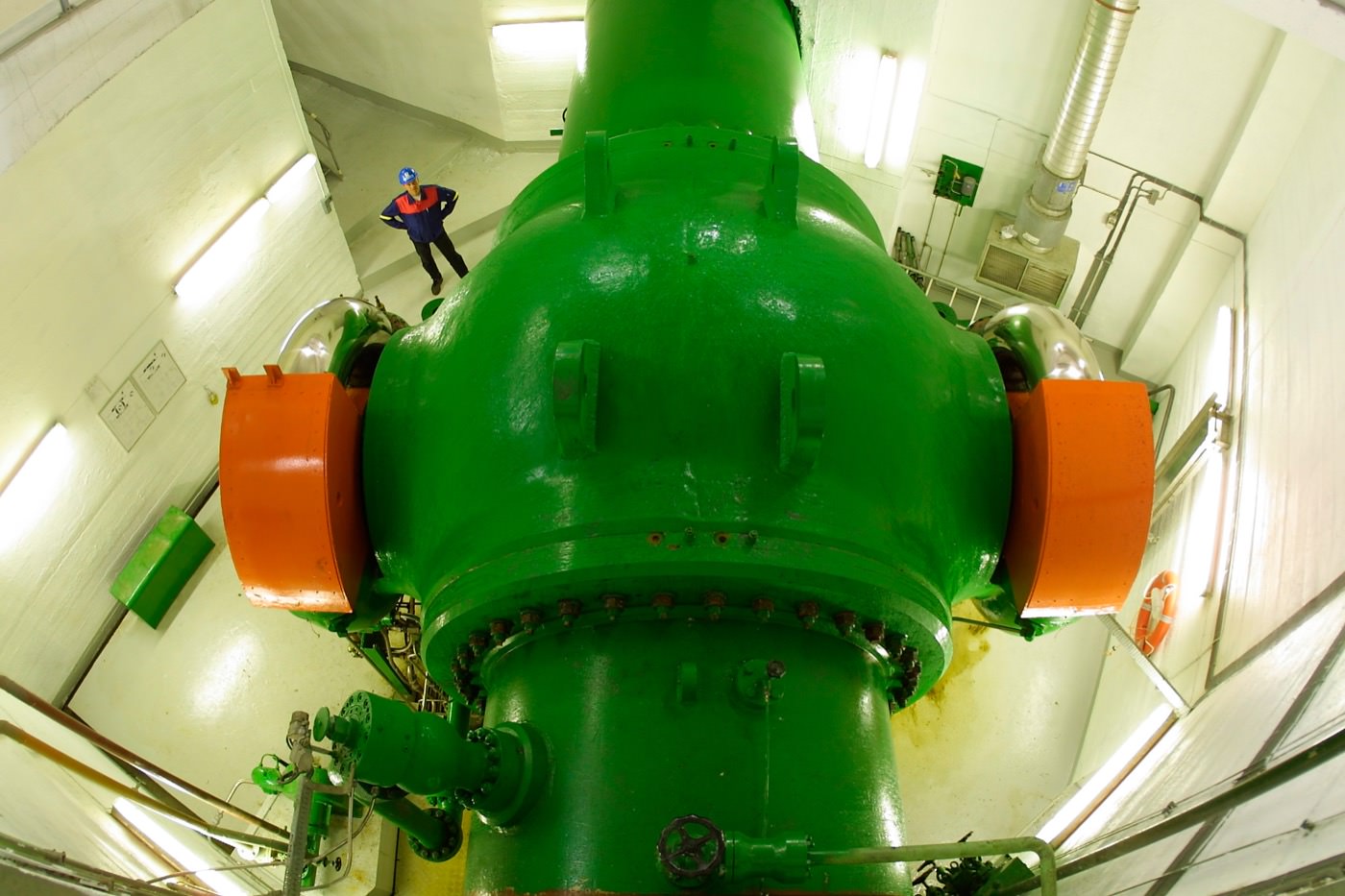

From the breakthrough for the penstock to the brand-new power station built inside the mountain during the rehabilitation of Nedre Røssåga power plant from 2012 to 2016. The modernisation of Nedre Røssåga is among the largest hydropower projects in Norway in the 2000s.

After the completion of the rehabilitation of the Nedre Røssåga hydropower plant in Nordland, production increased, equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of more than 100,000 Norwegian households.

The Nedre Røssåga hydropower plant, which was commissioned in the 1950s, is located in Hemnes municipality in Nordland. Rehabilitation and expansion of the facility started in the spring of 2012. Nedre Røssåga reopened in 2016, after one of the largest rehabilitation projects in Norway in over 15 years.

By increasing the capacity of water tunnels and harnessing the power of new equipment, more power can be generated from every drop of water that passes the turbines. When Nedre Røssåga reopened, it had become one of Norway's largest hydropower plants, with a production of 1.6 per cent of the country's total production.

In addition to increased power production, the rehabilitation project improved the environmental conditions in the Røssåga watercourse with expanded spawning areas for salmon and sea trout.

When the Nedre Røssåga project was completed, work continued to upgrade the Øvre Røssåga power plant. The two Røssåga plants will be able to produce large amounts of hydropower for another 50 years.

Located 65 kilometres southeast of Tirana, the Banjë hydropower plant in Albania was officially opened in August 2016.

Banjë hydropower plant in Albania

Banjë is one of two hydropower plants in Statkraft’s Devoll hydropower project. The second hydropower plant, Moglicë, enters into operation in the first half of 2020.

While delivering renewable energy to the Albanian grid, the project has also contributed to local infrastructure development including 100 km of new roads and as well as environmental and social measures locally.

Together, the two power plants have increased Albania’s electricity generation by 17 percent, strengthening Statkraft’s position as Europe’s largest generator of renewable energy.

New disruptive technologies drove the development within the energy sector and start-ups were emerging as market leaders. In 2015, Statkraft established the venture capital unit Statkraft Ventures GmbH to fund and develop new companies.

By partnering with dynamic start-ups, Statkraft could play an active role in shaping the energy markets of the future, leveraging the synergies between the start-ups and the Statkraft Group.

In 2015, Statkraft established the biofuel company Silva Green Fuel together with the Swedish company Södra. Biofuels are climate-friendly and offer a fast solution to cutting emissions.

Consolidation and targeted growth also included the development of new business models. The biofuel company Silva Green Fuel, owned 51 percent by Statkraft and 49 percent by the Swedish forest industry company Södra, was formed at the beginning of 2015 to produce second-generation biofuel from forest-based biomass waste at a plant in Hurum in Viken County.

Statkraft saw biofuel as an exciting business opportunity in renewable energy and an important contribution to achieving national and international targets for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector. Wood waste from forestry can be converted to fuel in a short time, and bioethanol from Scandinavian forests has a climate benefit of over 80 percent. Biofuels are therefore climate-friendly and offer a fast solution to cutting emissions.

In 2017, Silva Green Fuel decided to build a demonstration plant for advanced biofuel in Norway.

Second-generation biofuels

- Fuel produced by renewable materials such as wood, straw or seaweed

- A climate-friendly alternative to fossil fuels

- When biofuels are burned, they release CO2 as conventional gasoline and diesel do, but this CO2 is part of the natural carbon cycle already in the atmosphere and therefore does not contribute to the greenhouse effect.

In 2015, Statkraft entered a phase of consolidation and targeted growth, prioritising refurbishments of Nordic hydropower plants, growth in onshore wind and focused international hydropower projects and acquisitions.

In a continuation of the rehabilitation efforts launched in 2014, Statkraft made a major investment decision to upgrade the Øvre Røssåga hydropower plant in Northern Norway to fully utilise its potential.

Statkraft also expanded its onshore wind capacity in Europe, starting construction of the Andershaw onshore wind farm in Scotland which became operational in 2017, and finalising the wind farm construction projects in Sweden with the completion of Björkhöjden wind farm.

In South America, Statkraft actively strengthened its position as a leading international supplier of renewable energy. The Cheves hydropower plant was opened, bringing Statkraft’s total annual renewable power production in Peru up to around 2.5 TWh. Statkraft continued building industrial scale in South America through hydropower acquisitions in Chile and Brazil.

The completion of the new Kargi hydropower plant in Turkey marked an important milestone for Statkraft’s presence in the country. With Cakit and Kargi, Statkraft now provided more than one percent of Turkey’s annual hydropower generation.

Construction of Andershaw wind farm in Scotland.

In 2014, extensive work began to rehabilitate and upgrade older hydropower plants in Norway and Sweden.

In 2014, SN Power's activities in South America and South Asia were taken over by Statkraft, and Statkraft sold power plants in Finland and ownership stakes in wind power in the UK. In Norway, an agreement to swap hydropower plants was negotiated, and new hydropower plants and district heating plants came online. At the same time, new wind farms were commissioned in Sweden and the UK. There was also considerable activity to rehabilitate and upgrade older hydropower plants in Norway and Sweden, and Statkraft had a number of hydropower plants under construction internationally.

Efforts to rehabilitate the Tysso 2 power plant in Hordaland began in 2015, along with Lio in Tokke in Vestfold and Telemark County. Mågeli power station and Skjeggedal pumping station in Vestland were also upgraded during this period. Major rehabilitation of Eiriksdal and Makkoren were recently completed. Planning of rehabilitating Nore in Viken also started, and construction of a new power plant, Ringedalen, in Ullensvang Municipality, was approved to proceed.

Statkraft's strategy is to develop and maintain Norwegian hydropower through profitable and environmentally friendly development and rehabilitation projects.

Nedre Røssåga power plant was modernised and upgraded for future production.

Following several years of project development in a joint venture with Austrian company EVN, Statkraft acquired all shares in Devoll Hydropower Sh.A. in 2013. Statkraft then decided to start the construction of the Devoll hydropower project, including the two hydropower plants Banjë and Moglicë.

The Devoll project was an important part of Statkraft's investments in international hydropower, both securing renewable energy and development in Albania and strengthening Statkraft’s position as Europe's largest producer of renewable energy. The Banjë hydropower plant in Albania came into operation in 2016 and Moglicë will start operation in 2020.

Banjë reservoir, Albania

In 2013, Statkraft and the Norwegian Investment Fund for Developing Countries (Norfund) agreed to restructure and expand their partnership in renewable energy.

The two companies had established Statkraft Norfund Power Invest (SN Power) in 2002. The aim of the agreement in 2013 was to create a leading international community of hydropower expertise based on Statkraft, SN Power and the subsidiary Agua Imara, which was established by SN Power and Norfund in 2009. Statkraft integrated operations in Peru, Chile, Brazil, India and Nepal into its portfolio, while SN Power and Agua Imara were merged into an organisation to continue developing hydropower projects in emerging markets in Central America, Africa and Southeast Asia. In 2017, Statkraft sold its shares in SN Power to Norfund, while Norfund sold its shares in Statkraft IH AS (SKIHI) to Statkraft. Statkraft has continued to develop hydropower and wind assets in South America and India and has also expanded into the energy trading business in these markets.

The Sheringham Shoal wind farm is located about 20 kilometres from North Norfolk off the east coast of England. The spectacular wind farm can supply 220 000 British households with pure energy.

The Sheringham Shoal wind farm has 88 turbines.

Since the early 2000s, wind power has contributed significantly to the increase in renewable energy production in the world. Statkraft and Statoil teamed up as equal partners to build Sheringham Shoal, one reason for the partnership being to combine Statkraft's energy market expertise with Statoil's offshore expertise.

Construction began in 2010, and the result was spectacular. When completed, Sheringham Shoal was the world's third-largest offshore wind farm, consisting of 88 wind turbines with 80-metre-high turbine towers and 52-metre-long rotor blades. The enormous wind turbines are spread over an area of open sea covering 35 square kilometres and can supply 220 000 British households with pure energy.

Crown Prince Haakon opened the wind farm on 27 September 2012. Statoil and Statkraft also cooperated on the Dudgeon offshore wind farm about 20 kilometres northeast of Sheringham Shoal. Masdar was also a partner in this project. Dudgeon would provide renewable electricity to a further 400 000 UK households. In 2015, Statkraft decided to halt investments in offshore wind and divested all its holdings by the end of 2017.

In 2011, Statkraft completed one wind farm and began building two new ones in Sweden and one in Scotland. That same year, the first power was supplied from the offshore wind farm Sheringham Shoal off England's east coast.

Statkraft continued to invest in international hydropower and wind power, and in 2009 the company entered the Turkish market. This would prove to be a key market for the company.

During the first decade of the new millennium, Statkraft established itself in countries such as Albania, India, the Philippines, Peru, Brazil, Chile and Turkey. Turkey emerged early as a highly attractive investment candidate. The country had vast hydropower resources and an energy market among the fastest growing in Europe.

In 2009, Statkraft acquired the Turkish energy company Yesil Enerji and took over an exciting portfolio of power projects. The hydropower plant Cakit in Adana Province began commercial operation in June 2010 and was officially opened by Turkey's Energy Minister in October the same year.

The development of Statkraft's second hydropower project in Turkey, Kargi, began in 2011 near the town of Osmancik in Corum Province. The construction of the third project, Cetin, started in 2012 on the Botan River, a tributary of the Tigris in the south-eastern part of the Antolia region. In May 2015, the power plant in Kargi was ready for operation and the opening confirmed that Statkraft had a long-term investment strategy for Turkey. In just a few years, Turkey had grown to become one of the company's priority countries within international hydropower and power trading. Cetin was by far Statkraft's largest hydropower project outside Norway. The Cetin project experienced repeated difficulties with its contractors and was sold in 2017.

Barren hydropower plant

- Production started in May 2015

- Located near Osmancik in Corum province in northern Turkey

- Was Statkraft's second Turkish hydropower plant after Cakit, which opened in 2010

- Taking advantage of a 75-metre drop in the country's longest river, the Kizilirmak

- Has an installed capacity of 102 MW and can produce 467 GWh annually

Statkraft's position as Europe's largest renewable energy company was strengthened in 2009. Several renewable technologies were explored, and Statkraft teamed up with Statoil to build the Sheringham Shoal wind farm off the east coast of England.

By the end of 2009, Statkraft had employees in more than 20 countries and was Europe's largest producer of low-carbon energy from water, wind and gas power. The Group was also active in research and development in other forms of energy, such as marine energy, osmotic power and solar power. At Tofte in Hurum Municipality, a pilot plant was built to harness the osmotic energy generated when salt water and fresh water meet, but the project was cancelled in 2014.

Statkraft also developed solar power in Italy, but in 2011 made a strategic decision not to proceed with solar power at that time. In Scotland, Statkraft was granted a licence to build the Berry Burn wind farm, and the company joined forces with Statoil to establish one of the world's largest offshore wind farms, Sheringham Shoal, off the east coast of England.

The trend in Europe after the millennium was for large power companies to merge in order to become more competitive. An asset swap agreement with German E.ON made Statkraft Europe's largest producer of renewable energy.

When the Swedish market was liberalised in 1996, Statkraft acquired 5.1 per cent of the Swedish company Sydkraft. Statkraft later increased its ownership stake in this company and by 2004 owned 44 per cent, while German E.ON AG (formerly Preussen Elektra), owned 55 per cent.

In 2008, Statkraft and E.ON AG entered into an agreement whereby Statkraft swapped its 44.6 per cent ownership in E.ON Sverige AB (formerly Sydkraft) and a Swedish hydropower plant for a third of E.ON Sverige's hydropower production. The transaction had an estimated market value of NOK 25 billion and gave Statkraft 39 hydropower plants and five district heating plants in Sweden, two gas-fired power plants, shares in two biomass power plants and 11 hydropower plants in Germany, a hydropower plant in the UK, a gas storage contract and power supply contract, and 4.17 per cent of the shares in E.ON.

It was no secret that Statkraft also harboured ambitions for strong growth outside Europe.

The transaction made Statkraft Europe's largest producer of renewable energy, marking 2008 as the year of Statkraft's international breakthrough. It was no secret that Statkraft also harboured ambitions for strong growth outside Europe.

Wind power was a rapidly growing market in Europe at this time, and the United Kingdom stood out as a particularly attractive market for Statkraft.

The UK has very favourable natural conditions for wind power. In addition, the British government has introduced favourable incentive programmes for renewable energy. Statkraft opened the office of its subsidiary Statkraft UK Ltd in London in 2006. The company had already been active in Britain for three years, mainly through a series of partnerships to develop wind power.

In 2006, Statkraft was involved in several wind power projects and was regarded as a significant participant in the UK energy trading market. The company wanted to expand, and in the following years Statkraft UK spearheaded efforts to develop the Group's business opportunities in the country. Statkraft also made major investments outside Europe. In 2006, Statkraft was involved, through SN Power, in power projects in countries such as Peru, Chile, the Philippines, Nepal, India and Sri Lanka. Statkraft also worked on hydroelectric projects in south-eastern Europe through its offices in Montenegro, Albania and Turkey.

The Berry Burn wind farm is located near Inverness in northern Scotland. The wind farm has 29 wind turbines.

In 2005, Statkraft joined the Allain Duhangan hydropower project in India. The project showed the huge potential for hydropower in India, but also how challenging hydroelectric construction projects in developing countries can be.

Statkraft was the first foreign company to invest in the hydropower sector in India.From the construction of the Allain Duhangan hydropower project in the Kullu Valley, Himachal Pradesh state, northern India.

In 2005, Statkraft’s former subsidiary SN Power decided to join the Allain Duhangan hydroelectric project in India in partnership with the Indian company Bhilwara. The project would prove to show how challenging hydroelectric construction projects in developing countries can be. Organisational and technical problems led to substantial delays and cost overruns, but health and safety conditions posed the biggest challenge.

During the construction period, which lasted until 2012, a total of 16 persons lost their lives. Due not least to the lessons learned from Allain Duhangan, SN Power and Statkraft committed substantial resources to improving the health, safety and environmental conditions at all their international hydropower projects.

Since the start of commercial operations in 2012, the 192 MW Allain Duhangan hydropower plant has delivered around 800 GWh of renewable energy annually, giving an important contribution to greener electricity in India.

The Philippines was another country where SN Power committed itself during this period, making its first investment there in 2006.

In 2005, Statkraft decided to build two gas-fired power plants, Knapsack and Herdecke, in Germany. It was the biggest investment for the company since the early 1990s.

King Harald opened Knapsack, Statkraft's first gas-fired power plant outside the Nordic region on 18 October 2007.

In the spring of 2005, Statkraft decided to build two gas-fired power plants in Germany: Knapsack with 800 MW of capacity outside Cologne, and Herdecke with 400 MW south of Dortmund. Statkraft would build and own Knapsack alone, while Herdecke was a collaborative project with the German energy company Mark-E. This investment in gas power in Germany was Statkraft’s biggest since the development of Svartisen hydropower plant in Norway in the early 1990s. The idea was that captive power production on the European continent could support trading operations at the offices in Düsseldorf and Antwerp.

Both plants were commissioned around two years later in autumn 2007, and this was celebrated as a milestone. Up until that point, the only production Statkraft had owned in Europe was in the Nordic region. Now the company had established a significant position for itself on the European continent, and the goal was to develop even more. During the years after 2000, as a consequence of the sudden rise of climate policy, many believed that gas power would have a key role as a transitional solution on the way towards a renewable society. Gas power is far cleaner than coal, and the perception was that gas should replace coal until renewable forms of energy could fully replace carbon-based power production.

The German gas power investment marked a shift in Statkraft's growth strategy. One issue was the green company Statkraft investing in fossil fuel power production, although gas power in the European context could be justified in terms of climate policy. Another issue was that ownership and involvement in the German gas power plants signalled a new form of expansion that would become dominant over the next decade. From around 2005, the company began to focus more on organic growth, i.e. developing production capacity alone instead of with others or through purchases. After 2005, all talk of mergers and acquisitions was almost over. The company began investing heavily in the construction of power production throughout Europe. The gas-fired power plants in Germany were one example of this commitment.

Gas-fired power plants

- Have the lowest CO2 emissions of all power plants based on fossil fuels

- Can replace far more pollutive electricity production based on oil and coal

- Generate electricity using gas turbines and steam turbines

- Statkraft owns gas power plants in Germany and has ownership interests in plants in Germany and Norway

In 2002, the Norwegian Government introduced significant changes in the relationship between the state and Statkraft. From 1 October 2004, Statkraft was reorganised as a limited company, wholly owned by the state.

The corporate group Statkraft AS was established with the strategic goal of becoming a European leader in environmentally friendly energy. Late in 2004, group management in Statkraft decided to establish a business area called "New Energy." The business area was to identify and assess environmentally friendly forms of energy and projects in Europe in which Statkraft could get involved.

The establishment was part of a larger reorganisation aimed in part at assembling the professional communities of people who worked with new technologies and business development. However, it also reflected an ambition to intensify and focus efforts on organic growth. New Energy initiated an extensive survey of investment opportunities in Europe, and the results of the project were ready early in the summer of 2005.

In keeping with Statkraft's environmental profile, the working group had limited themselves to considering three energy sources: wind, water and gas. Wind and water were clean, renewable and unproblematic. Gas could be said to lie in a grey area, but was far cleaner than coal, for example.

Wind power became a new and important business area in the early 2000s. Statkraft's first wind farm was opened on Smøla Island in Møre and Romsdal County in 2002.

In 2002, King Harald cut the ribbon and officially opened the first construction phase of Norway's largest wind farm on Smøla Island, 30 kilometres north of Kristiansund in Møre and Romsdal County. It was a milestone celebrated with great fanfare. Twenty wind turbines up to 70 metres high with wingspans of up to 80 metres would supply electricity to about 6 000 households.

"The development and all it brought with it has created a new momentum and optimism for the entire island"

- Former Smøla mayor Iver Nordseth

In 2005 Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland opened the second construction phase of the wind farm. Today the wind farm on Smøla has a total of 68 wind turbines and an annual power production of 450 GWh. This is equivalent to the average consumption of 22 500 Norwegian households. On days with good wind, Smøla wind farm alone can supply the entire county of Møre and Romsdal with electricity. Smøla was the beginning of Statkraft's commitment to new investments in wind power. Later further investments were made in Norway, Sweden and the UK, both onshore and offshore.

Wind power is one of the most environmentally friendly forms of large-scale power production, and Norway had vast wind resources that were almost completely untapped. Wind power would create local, national and international jobs, and provide income to the community. The wind farm on Smøla proved this point. It gave Smøla Municipality a real boost; the population increased, along with the number of jobs and the number of beds available for overnight accommodation. This was because Smøla wind farm became a tourist attraction.

In a survey in 2007, 72 per cent of the island's inhabitants responded that they had a positive view of the wind farm and that they were proud of it. In 2004, Hitra wind farm opened in Sør-Trøndelag, and in 2006, they were joined by Kjøllefjord wind farm in Finnmark. In 2015 Statkraft had a total of 109 windmills in Norway.

Smøla wind farm

- Wind farm with 68 turbines on Smøla Island in Møre and Romsdal County

- Largest wind farm in Norway and largest onshore wind farm in Europe

- Covers 18 square kilometres

- Built in two phases, which opened in 2002 and 2005

- Maximum production capacity is 150 MW

- The wind farm generates 450 GWh per year on average, equivalent to the average consumption of 22 500 Norwegian households

- Wind turbines are up to 70 metres high

Along with Norfund, the Norwegian Investment Fund for Developing Countries, Statkraft created the international power company Statkraft Norfund Power Invest (SN Power) in 2002. The company was formed to promote economic growth and sustainable development in new and emerging markets.

SN Power was a continuation of efforts that Statkraft began in the 1990s with projects in Laos and Nepal. The establishment of SN Power was a significant revitalisation of the commitment to hydropower outside Europe. The company would specialise in building hydropower projects in developing countries, and Latin America was chosen as an interesting area to focus on.

The region had major potential for hydropower, but only a small portion had been developed. During the early years, SN Power established itself in Chile, Peru, India and the Philippines through new hydropower development projects and acquisition of existing power plants. SN Power would maintain high social, ethical and environmental standards, and not engage in activities that could be controversial. This had several consequences, including for which type of hydropower projects the company could choose.

Generally speaking, the company could not invest in reservoir power plants like the type most common in Norway, because these often involved damming up larger areas, resettlement, and impacts on the water flow in rivers. The primary focus was to be on "run-of-river" power plants, meaning plants that more or less just used only the natural flow of the river.

Not only would SN Power generate income for its owners, but the company would also contribute to sustainable social and economic development in poor countries.

SN Power would also follow the same high standards for health, safety and the environment internationally as Statkraft followed in Norway. "Powering development" was a phrase that was widely used in the early promotion of the company. Not only would SN Power generate income for its owners, but the company would also contribute to sustainable social and economic development in poor countries. With the advent of SN Power, investments outside Europe took a much more central role in the company's strategy. Today, Statkraft develops hydropower and wind power in countries such as Peru, Chile, India, Nepal, the Philippines and Turkey through SN Power.

SN Power

- Created in 2002 by Statkraft and the development fund Norfund

- Established to promote economic growth and sustainable development in new and emerging markets

- Specialised in building hydropower projects in developing countries

- Focused primarily on "run-of-river" power plants but also on wind power

- Has power plants in Peru, Chile, India, Nepal, the Philippines and Turkey

Statkraft entered the new millennium with the strategic goal of becoming Europe's leading pure energy company. This would be achieved through investments in climate-friendly power generation and new energy sources, alone or in partnership with others.

From the construction of SN Power's river plants La Higuera and La Confluencia in Chile.

By the beginning of the new millennium, Statkraft already had a broad portfolio within hydropower, wind power and district heating, but it had big plans for new mergers and acquisitions in northern Europe and other parts of the world.

There was a trend in Europe for big power companies to merge together into even larger entities, and there seemed to be a widespread notion that survival and success were dependent on size. Put simply, there were two choices: eat or be eaten.

This logic also affected the Statkraft organisation, which had no desire to become a marginalised power company on the outskirts of Europe. On the contrary, the company entered the twenty-first century highly focused on international growth and strategic positioning. Contacts were made with a number of European companies, discussions were held about many possible types of cooperation, and some of these led to exploratory discussions about alliances and mergers. Opportunities were also explored for mergers and acquisitions outside Europe. "International Hydropower" had become one of Statkraft's strategic focus areas.

From the late 1990s, new horizons opened up for Statkraft. Climate change and globalisation created major challenges, but also new and exciting opportunities.

A key trend during this period was the sudden rise of climate policy. Both nationally and internationally, focus was increasingly placed on climate change and global warming. The Kyoto Protocol in 1997 was the first tangible sign of this new development, where many of the world's richest countries committed themselves to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Climate change was also a strong motivation for Statkraft. Increased use of pure energy from water, wind and sun can help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, and the shift towards renewable energy offered new business opportunities for Statkraft.

The shift towards renewable energy offered new business opportunities for Statkraft.

In the autumn of 1998, Statkraft opened its first office for power trading in continental Europe. A similar trading office opened in Dusseldorf a year later.

Statkraft opened a trading office in Düsseldorf in 1993. This picture shows the company's offices in the city.

The Netherlands' power market was the first in continental Europe to be deregulated, and Statkraft established itself in Amsterdam to access the new markets that opened up. The office initially traded with large-scale customers. The following year, in September 1999, Statkraft opened a similar trading office in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Armed with experience from Scandinavia and the Netherlands, Statkraft also identified significant business opportunities when the power market in Germany was rapidly deregulated. Up until then, Statkraft had been associated more with power production than with power trading. However, power trading as a business area grew rapidly and became increasingly important, and Statkraft soon established a presence in international markets where power and power-related products were bought and sold.

Statkraft soon bought into BKK and Scanenergi, and the company saw the beginning of a gradual phasing out of industrial contracts, i.e. contracts imposed by the Storting that secured Norwegian industry affordable power. The company's positive earnings trend continued. Flexible production management combined with market analysis led to steadily improving financial results.

Power trading as a business area grew rapidly and became increasingly important for Statkraft.

Power trading

- International markets were developed for buying and selling power and power-related products

- Market prices vary and are influenced by several factors

- Cold periods or heat waves can trigger underproduction or overcapacity of power

- By analysing vast amounts of market data, one can predict how prices will change

- An important part of Statkraft's job is knowing when it pays to buy or sell a product so as to generate the most value for its clients

- Clients range from small-scale producers looking to sell from their own power plants through to large-scale industrial businesses that need a constant power supply and to companies delivering power

The years after 1996 were characterised by expansion through significant acquisitions of ownership stakes in other companies. The first foreign acquisition was made in the spring of 1996 when Statkraft acquired a small stake in Sydkraft, Sweden's second-largest power company.

Khimti Khola River in the Dolakha district, Nepal

The background for the acquisition was the deregulation of the Swedish power market in the same year. Statkraft realised it would be profitable to invest in Swedish hydropower. Sweden and Norway became a common energy market with extensive trading through Nord Pool, the world's first international power exchange. This changed the character of power trading from long-term, bilateral agreements to exchange trading with spot price, futures contracts and other financial instruments. The same year saw the completion of the power plant on the Khimti Khola River in the Dolakha district around 100 kilometres east of Kathmandu in Nepal, of which Statkraft was the majority owner.

In 1994, a 260-kilometre-long subsea power cable was laid across the bottom of the Baltic Sea between the cities of Trelleborg, Sweden and Lübeck, Germany. The power cable would play a crucial role in integrating the Swedish and German power markets.

Baltic cable

Connecting different European regions was an important step towards further developing the European power market. The cable was originally owned by the Swedish-based company Baltic Cable, but Statkraft eventually acquired the ownership of the company. As owner of Baltic Cable AB, the company that owned, operated and maintained the cable, Statkraft gained direct access to the European power market.

Statkraft, Hydro and Statoil joined forces in 1994 to create Naturkraft AS with a view to using Norwegian natural gas to produce electricity. Plans to build plants at Kollsnes in Hordaland and Kårstø in Rogaland were abandoned five years later, but in 2005 a decision was made to proceed with Kårstø.

Kårstø Gasskraftverk

Naturkraft, now owned 50/50 by Statkraft and Statoil, opened Norway's first commercial gas-fired power plant in 2007. In 1994, Statkraft entered into power exchange agreements with Dutch SEP and German Preussen Elektra. Power markets in Europe were becoming progressively integrated.

In Norway, the construction of the Svartisen power plant was the only significant hydropower project during this period.

In 1987, the last of Statkraft's large-scale domestic construction projects began. In 1993, Svartisen power plant was put into operation. During these years of further development, the power industry was turned upside down. Statkraft made the transition from monopoly to competition, from planned to market economy, and from power deficit to power surplus, as well as a hegemonic shift from engineering to economics.

Svartisen power plant is situated by the Nordfjorden fjord in Meløy Municipality in Nordland County. It harnesses meltwater from Norway's largest glacier, Svartisen, through one of Norway's two subglacial intakes. During construction, it proved to be extremely difficult to determine the exact location of the glacial rivers.

A special laboratory was built below the adjoining Engabreen glacier, where researchers from several countries could study the glacier's movements and characteristics. Svartisen Subglacial Laboratory is the only facility in the world where researchers can conduct studies under a 200-metre-thick ice mass. Svartisen power plant produces enough electricity to supply a city of around 100 000 inhabitants.

Svartisen power plant

- The power plant is located beside the Nordfjorden fjord in Meløy Municipality in Nordland County.

- Became operational in September 1993

- Situated by Svartisen, Norway's second-largest glacier

- Meltwater from the glacier is important for operations

- Storglomvatnet was dammed up in 1998 and now serves as the reservoir for the power plant

- Some of the water previously directed to Glomfjord power plant is now sent to Svartisen

- Produces enough electricity to supply a city of around 100 000 inhabitants

The period around 1990 marked the start of Statkraft's commercial and international history. In 1992, Statkraft was split into two state-owned enterprises.

From the state's first waterfall acquisition in 1895 to the formation of the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) in 1921 and then Statkraftverkene in 1986, power generation and transmission were organised as one public utility. A new energy law in 1990 paved the way for a free power market and competition in the sale of power, while power transmission remained a monopoly. As a consequence of the new energy law, Statkraft was divided into two state-owned enterprises in 1992. The new Statkraft was made responsible for production and sales, while Statnett took care of distribution. Norway became a pioneer in the liberalised power markets, with state-owned Statkraft taking a leading role.

Hydropower development in Norway wound down, and Statkraft entered an era dominated by operations and markets. 1990 proved to be a watershed year.

With no prospect of any new large hydropower projects in Norway, it became more important to streamline operations and the power grid to produce electricity when it provided most value. The power markets were deregulated and liberalised. A new energy law in 1990 provided the framework for how power supply in Norway should be organised. The law paved the way for a free energy market and competitive power trading, while power transmission itself remained monopoly-based. With the new law, Norway became a pioneer in the deregulation of power markets, and Statkraft faced a new era as a commercial power company and international player. The Energy Act also led to a reorganisation of Statkraft.

During the 1980s, traditional hydropower development began to wind down in Norway. One of Statkraft's last major developments was Ulla-Førre in Rogaland County.

King Olav V opened Kvilldal power plant, one of the Ulla-Førre plants, on 3 June 1982, with his name engraved in stone at the power plant the same year.

The development of Ulla-Førre took place at a time when views about locating hydropower plants in the mountains were changing, and the developers were well aware of the changing times. However, despite Ulla-Førre being the largest state-owned hydropower development at the time in Norway, there was little protest. Ulla-Førre was planned and implemented without meeting significant resistance from nature conservationists or environmental activists. The power plant involved the joint development of a number of river systems flowing into the Otra River at Kristiansand in the south and into the Suldalslågen River at Sand in the northwest. The facility included two power plants: Hylen and Kvilldal; two pumped-storage plants: Saurdal and Hjorteland; and one combined plant: Stølsdal.

Ulla-Førre was completed in 1988 at a cost of NOK 7.8 billion, and its 20 dams and 125 kilometres of tunnels made it the largest facility of its kind in northern Europe. The project included the longest tunnels and the largest cross-sections – up to 175 square metres – ever built. One of the largest tunnels was big enough to house a four-storey apartment building.

Ulla-Førre

- One of the largest hydropower facilities of its kind in northern Europe

- The development of the power plant took place in the period 1974-1988

- The plant draws water from a 2 000 km² large catchment area in central Ryfylkheiene

- This includes the artificial Blåsjø Lake, which is dammed by some of the largest dams in Norway

- The group of power plants making up Ulla-Førre include Kvilldal, Saurdal, Hylen and Stølsdal

In 1986, Statkraft was spun off from NVE after lengthy political debate. From that point on, Statkraft became a management company under the supervision of the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.

NVE building

One reason for the separation was the need for greater independence from politics and the ministry in order to operate more effectively. The ability to offer competitive salaries and working conditions was another key motive. The separation was underscored with a separate logo and a new and more modern name, Statkraft. It was important for the new company's management to be seen more as a modern company and less as a traditional government agency.

In the same year that the contentious Alta development was under way, construction of another power plant was completed at the head of the Hardangerfjord.

Sima power plant

Harnessing the high waterfall from the Hardangervidda plateau to Eidfjord proved challenging, but the Sima plant from 1980 still stands as one of the largest hydropower plants in Europe. The plant's machine room, situated 700 metres inside the mountain, is 200 metres long, 20 metres wide and 40 metres high.

No other power development project in Norway has sparked so much controversy and emotion or created so much political drama as the Alta development.

Plans for the development quickly became highly controversial, and the issue came to a head in 1979. The people’s movement against development of the Alta Kautokeino river system organised demonstrations in Oslo and Alta, and at the construction site in Alta, a thousand protesters faced off against hundreds of police officers in a confrontation that received wide press coverage. Angle cutters were used against links and chains when the Government decided to fight fire with fire.

A key argument against the development was the Sami people's indigenous rights to land, water and grazing areas for reindeer. Norway's Supreme Court dismissed the claim that this issue had been inadequately addressed, and the Alta power plant was finally built and put into operation in May 1987. The intensity of the environmental protest led to more stringent standards for river system development, and the final design of the power plant was impacted by the new principles that emerged from the debate over its construction. In retrospect, the Alta campaign stands as the prime symbol of resistance to Norwegian hydropower development, even more so than the Mardøla campaign ten years earlier.

The Alta development

- Hydropower plant in Sautso in Alta Municipality in Finnmark County

- Began operations in May 1987

- The development of the Alta-Kautokeino river system was controversial and triggered Norway's largest civil disobedience campaign

- The power plant is built 40 kilometres from the outlet of the Alta River

- In the course of its 170 kilometre-long run, the river takes in water from a

- large part of the Finnmarksvidda plateau

- The power plant makes use of a water drop of 185 metres from the 18 kilometre-long Virdnejávri Lake reservoir

Around 1980, the state owned about a third of Norway’s installed capacity for electricity generation. New methods to calculate the future value of water stored in reservoirs heralded a trend towards market-based power pricing.

A kilowatt became a commercial commodity in itself. However, critical voices protested against the extensive construction of power plants, and new projects became more difficult to implement.

Throughout the 1980s, the level of investment in new power production projects dropped dramatically, and it seemed that the Norwegian hydropower boom was nearing its end. There were few waterfalls left to develop, and obtaining permission to harness them was becoming more difficult.

Norwegian society could now afford to leave its waterfalls untouched, and increasingly chose to do so. For Statkraft this slowdown happened fairly abruptly, since several major projects were completed almost simultaneously. In 1988, Statkraft put the finishing touches on four construction projects, including Alta in Finnmark and Ulla-Førre in Rogaland.

From the mid-1960s, protests and demonstrations against hydropower development grew in scope and strength. The Mardøla protest campaign led to a broad debate on development and conservation.

In the 1960s, hydropower development became more controversial, and political conflict increased. Terms like nature conservation, ecology and environmental policy came into daily usage, and nature conservationists and environmentalists protested against hydropower construction projects.

When it became known that the spectacular Mardalsfossen waterfall in Eikesdal in Møre and Romsdal was to be diverted into pipes, environmental activists gathered in the summer of 1970 to stop the construction machines. Carrying banners with slogans like "Stop the construction work" and "Mardøla must continue to flow to Eikesdalen", demonstrators gathered in a tent camp in the mountains between Nesset and Rauma Municipalities. They bolted themselves to rocks and chained themselves together to stop the trucks and bulldozers. This campaign of civil disobedience, inspired by Gandhi's philosophy of non-violence, managed to block the construction machinery for an entire month, and received considerable media attention in Norway and the rest of Europe.

Despite this resistance, the river system was eventually developed, but the Mardøla campaign generated a broader debate between hydropower development and concerns for nature and the environment. The campaign led to new definitions of nature conservation. Biological, ecological and aesthetic values were given more weight, and local considerations took on a greater role in the planning of hydropower projects. The Mardøla protest campaign's use of civil disobedience to back up demands for preserving pristine nature remains an important symbolic event, overshadowed only by the Alta protests ten years later.

Mardøla campaign

- The Mardøla campaign consisted of several protest actions in the summer of 1970 against hydropower development in Eikesdal in Møre and Romsdal County

- The campaign was an important symbolic event in the effort to preserve pristine nature

- The campaign gained prominence because the spectacular Mardalsfossen waterfall was to be diverted into pipes

- The river system was developed and Mardalsfossen is dry most of the year

- During a few weeks of the tourist season each summer, the original water flow is almost fully restored

The Mardøla campaign consisted of several protest actions against hydropower development in Eikesdal in Møre and Romsdal County.

In the 1960s, hydropower development became more controversial, and political conflict increased. Words like conservation, ecology and environmental policies came into daily usage, and nature conservationists and environmentalists protested against hydropower construction projects.

One of the reasons for these protests was the large-scale and intrusive nature of hydropower development projects in the early post-war years. The Norwegian mountains were full of places where power development had left ugly scars in the landscape, and the construction projects had major impacts on many communities.

From the mid-1960s, the protests and demonstrations against hydropower development grew in scope and strength, not least against government plans for new plants. Young people carried out protest actions against new projects, and concern for nature and the environment began to be taken seriously in the form of new laws and government institutions. The most important of these was the Ministry of Environment, established in 1972. Environmental and nature conservation gained a progressively stronger influence on the choice of river systems to be developed and on the planning of individual projects.

Protests and demonstrations against hydropower development, especially the construction of the Alta power plant, seen here, defined the next chapter of Statkrafts history.

The development of Tokke was the most extensive hydropower initiative in Norway up until that time. Its vast size made Tokke a symbol of the engineering feats Norway could achieve.

There was an acute need for electricity in the 1950s, and a unanimous Storting resolved in 1956 to build the Tokke power plants in Telemark, funded by the state, the municipalities, industry, and loans from the World Bank. Tokke 1 was completed in 1961, and by 1964 most of the large Tokke complex was finished, including a number of power plants built to operate in a coordinated fashion. This was Norway's most extensive hydropower development so far, and its vast size made Tokke a symbol of the engineering feats Norway could achieve.

The intake tunnels were up to 75 square metres wide, and a total of 15 dams and 16 reservoirs were constructed. The largest of the reservoirs, Songadammen on the Hardangervidda plateau, had a surface area of no less than 30 square kilometres. It was a major national achievement. Power production from the Tokke plants would be for general domestic consumption. It was large enough to meet the electricity needs of the entire city of Oslo, but it came at a price. The plant cost a total of around NOK 1 billion. The largest portion was provided by the World Bank, which at the time classified Norway more or less as a developing country. Tokke became the acid test for the World Bank's willingness and ability to provide loans for hydropower development in Norway.

When Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen officially started the turbines in 1961, the plant was the largest in Northern Europe. The power plant stood as a technological marvel. From there, six, and later eight, power plants were coordinated and controlled from one room in one operating centre, equipped with Norwegian computer technology. Despite its high price, Tokke quickly became profitable. The entire development increased electricity production in the country by no less than 10 per cent.

"Tokke will be highly significant for Norway’s economy, and as a small country we have reason to be proud of this huge project."

- Einar Gerhardsen, Norwegian Prime minister in 1961

Tokke power plants

- Eight hydropower plant in Tokke Municipality, Telemark County

- Built in four stages between 1959 and 1979.

- Located in the upper western branch of the Skiensvassdraget river system.

- Makes use of the water drop of 1 000 metres from Hardangervidda plateau down to Bandak

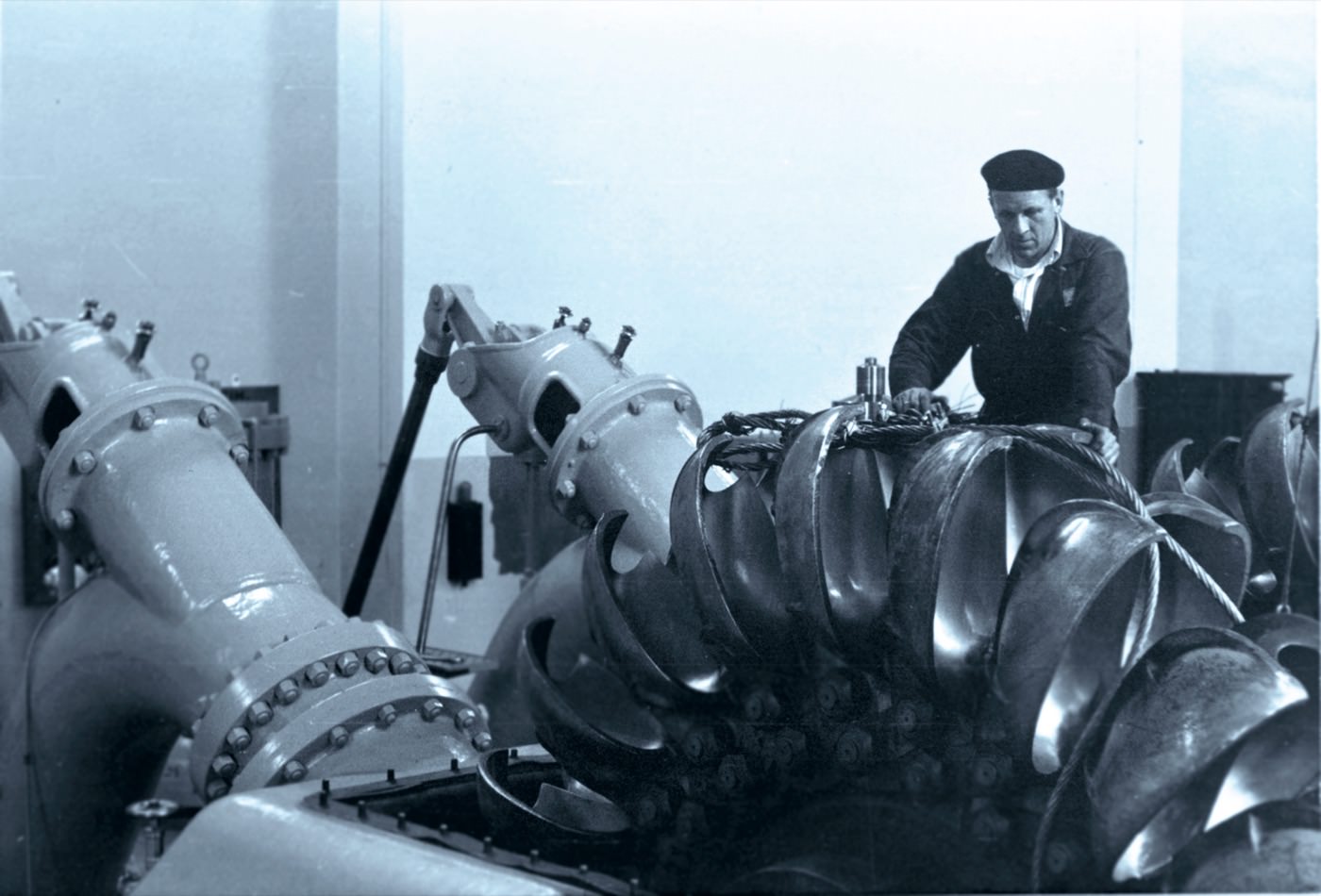

The lower Røssåga power plant was built to provide electricity for industrial development in Mo i Rana in Nordland, but already during the construction period it became clear that the need was greater than first expected. Consequently, construction of the upper Øvre Røssåga plant was initiated. The plants were put into operation between 1955 and 1958. The first construction in 1954 was linked to operating the ironworks in Mo i Rana, electricity for general use in 19 municipalities in Midt-Helgeland. In the 1960s, the aluminium smelter in Mosjøen also came on stream as a major consumer of power. The Røssåga plants together represented significant technical advances.

New construction equipment revolutionised construction and tunnel operations, and challenged workers and managers in new ways. The plant’s management praised the local construction workers for their ability to acquire knowledge and learn how to use the new equipment quickly and effectively. At its peak, the construction phase employed more than 1 100 people, and when operations began, there were three shifts a day. The construction project featured the country's first female tipper truck operator, but otherwise construction work was reserved for men, while women worked in the temporary site buildings. Architecturally, Nedre Røssåga follows the post-war trend, with features from 1930s functionalism.

Røssåga power plants

- The Røssåga power plants are located in Hemnes Municipality in Nordland County

- The power plants were built between 1955 and 1958

- Øvre Røssåga makes use of the water drop between Røssvatnet and Stormyrbassenget

- Nedre Røssåga makes use of the water drop between Stormyrbassenget and Korgen

The need for power for heavy industry and households had increased dramatically after the war, and the development of Aura power plant was one of the first major post-war construction projects.

The state became the owner and developer of Aura power plant in Møre and Romsdal in 1946, but it was not until 1951 that the Storting decided on full-scale development. The need for electrical power for industry and households had practically exploded after the war, and the state was in a hurry to build this plant. It had to be operating by 1954 because the new Sunndal Verk, later Hydro Aluminium, needed large supplies of power to produce aluminium in Sunndalsøra.

Aura power plant opened in 1953 after a construction period totalling eight years, and was one of the first major construction projects of the post-war period. Economic conditions in post-war Norway were difficult, and the plant was built with funds from the Marshall Plan launched by the United States in 1947 to support the reconstruction of post-war Europe. Aura was also the first state-built power plant with a machine room built inside a mountain. Architecturally speaking, the plant is representative of many post-war plants, with a simple reception building and more spacious machine rooms inside the mountain.

From 1950 to 1960, the state constructed large hydropower plants across the country. At the same time, a change occurred that represented enormous developments in technology and advanced engineering.

Aura power plant was the first state-built hydropower facility built inside a mountain.

Tre av de største vannkraftanleggene som ble påbegynt i denne perioden, var Aura-utbyggingen i Møre og Romsdal, Røssåga-anleggene i Nordland og Tokke-anleggene i Telemark. Den kraftkrevende industrien ga arbeidsplasser og valutainntekter. Vannkraften, sett som Norges arvesølv, gjorde storsatsingen på industri mulig, og Staten sikret rikelig tilgang på rimelig kraft til metallurgisk og elektrokjemisk produksjon.

Up until this point, the large power stations had been built as monumental cathedrals with magnificent architecture, towering in their natural landscapes of waterfalls and rivers. However, technological advances meant that power plants planned and built in this period acquired totally new dimensions. From the 1950s, major facilities were hidden inside mountains, primarily for reasons of emergency preparedness. Memories from the war were still fresh, but it was also far more practical to place intake tunnels inside mountains than in pipe trenches on the outside. This change represented a crucial development in technology and advanced engineering. Mountain power plants with large machine rooms provided architects with completely new challenges. As in the old plants, the machine rooms in some plants were still monumental, but the exterior design of the reception buildings was often much simpler. Aura power plant is one example of this construction design.

Expertise development and a pioneering spirit characterised the Norwegian state’s power plant developments after the war. No other period has been as challenging for the state's hydropower engineers and construction workers.

Man with turbine runner at Aura power plant. The first generators began operation in 1953.

Big ambitions, large plants, large machinery and the need to provide power to heavy industry, as it was called in those days, characterised public hydropower development in the post-war period. Many local communities also had to deal with major upheavals and challenges, but hydropower delivered major benefits in return.

After the war, the state took over a number of major power plants which the German occupying force had built or had begun building during the war. Several resolutions passed by the Storting (the Norwegian parliament) ensured that heavy industry would have access to abundant and inexpensive power. Norway needed to be built up, and energy-intensive metallurgical and electrochemical industries would ensure both export revenues and jobs. Power plants such as Mår in Rjukan and Tyin in Årdal were quickly completed to provide the necessary power to produce important export products such as fertiliser and aluminium. The country was undergoing a period of major expansion. The state's share of power production in Norway increased rapidly, from 10 per cent in 1945 to 27 per cent in 1965

On 20 September 1942, the British sabotage operation code-named Operation Musketoon put an end to the Germans’ plans for Glomfjord when two Norwegians, one Canadian and nine Britons blew up the pipe trenches and generators at the power plant.

A monument stands outside Glomfjord power plant in memory of the saboteurs' heroic efforts. The names of the saboteurs are carved in stone on a pillar outside the Glomfjord power plant.

In Norwegian war history, the operation is also referred to as the Glomfjord raid or the Glomfjord operation. The purpose of the operation was to cut the power supply to the Haugvik aluminium plant, which was critical to the German war effort. At the time, the plant was controlled by the German Nordische Aluminiumgesellschaft.

The German occupiers planned to develop the power station in order to expand the aluminium plant and thus increase production. Two Norwegians, Sverre Granlund (1918-1943) and Erling Magnus Djupdræt (1920-1942) from Kompani Linge participated in the sabotage action as local guides. They were the only Norwegians in the unit, which otherwise consisted of one Canadian and nine British commandos.

Under the command of Captain Graeme Black, the soldiers were transported from the Orkney Islands to Norway on board the French submarine Junon to carry out the sabotage mission. Sergeant Djupdræt was seriously injured by a bayonet during combat with German guards. He was transported to Bodø hospital but died two days later from his injuries. Seven of the saboteurs were captured by the Germans and later executed in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Four of the saboteurs, including Corporal Granlund, managed to escape and survived Operation Musketoon. Sverre Granlund died in 1943 when the submarine Uredd struck a mine in the Fugløyfjorden fjord in connection with the sabotage raid Operation Seagull. A monument now stands outside Glomfjord power plant in Nordland County in memory of the saboteurs' heroic efforts.

Glomfjord power plant

- Located in Meløy Municipality in Nordland County.

- Makes use of a water drop of 464 metres between Nedre Navarvatnet Lake and sea level

- First stage of construction was completed in 1920

- Some sections of the construction were damaged as a result of sabotage in 1942

- The entire project was completed in 1950

- Laid the foundation for the industrial community of Glomfjord

- A new mini power plant inside the old power plant was put into operation in 2014

During World War II, between 1940-1945, a number of new hydropower developments were initiated by the occupying forces, some of them to produce aluminium for the German aerospace industry. New transformers and more efficient transmission lines were also established across the country.

The saboteurs blew up the pipe trenches and generators at the power plant in 1942. The Germans wanted to expand Glomfjord power plant, but Operation Musketoon put an end to their plans

The electrification of Norway accelerated in the years before World War II in 1940-1945. Constantly improving transmission technology gradually provided a growing number of valleys, settlements and towns with access to electricity for buildings, street lights, railways and businesses. During World War II, a number of new hydropower developments were initiated, some of them to provide power to produce aluminium for the German aerospace industry. However, despite the initially comprehensive German plans for developing hydropower in Norway, little was actually realised in the war years.

Already in 1942, these ambitious plans were either scaled back or abandoned, and work at several of the plants was stopped. Norwegian and Allied sabotage and bombing of hydropower plants and factories, among them Vemork in Telemark and Glomfjord in Nordland, thwarted the armaments plans of the occupying forces. Most of the power plants established in those days are still in operation today.

A major economic downturn hit Norway hard in the interwar years, when the global depression spread. Between 1920 and 1930, industrial production fell by 30 per cent. The weak growth in electricity consumption during the 1930s hit the public power plants particularly hard.

Nore power plant in Eastern Norway and Glomfjord power plant in Nordland suffered major losses throughout most of the interwar period. Not surprisingly, this contributed to the gradual loss of political legitimacy of the commitment to public power production. Consequently, the state only built two power plants between 1920 and 1940; the wholly state-owned Nore plant in Buskerud and the Solbergfoss plant in Glomma in Østfold County, in cooperation with Kristiania Municipality.

A strong commitment to combining railway operations with electric power was the reason why the Storting (the Norwegian parliament) in 1916 decided to develop the Hakavik river system in Øvre Eiker Municipality in Buskerud County.

The power plant is a monumental building and almost exactly the same as when it was built in the 1920s.

Hakavik power plant was built on the east side of Eikeren Lake in 1922 to supply power to the Drammen railway line. This was the first national electrification of a railway in Norway, and marked an important milestone in Norwegian history. The construction period was very eventful, with strikes, brawls, shortages, assassinations, rationing and inflation. Despite inflationary periods, World War I and other tumultuous events, the first generators began operation in May 1922. The fourth and final generator became operational in March 1936, when the stretch of railway between Drammen and Kongsberg was also electrified.

The power plant itself, which for a long time was Statkraft's smallest, is a brick construction with a simplified and monumental structure in neoclassical style. Like other power plants of the period, it has a large building volume. The machine room, the plant's central space, has tall, arched windows with many panes of glass. The eastern gable still shows the camouflage paint the Germans applied during World War II. The camouflage was used to protect the building during the war, and underlines the importance of the power plant for the infrastructure of Eastern Norway. The fact that the plant was seized by German airborne troops on the first day of the invasion of Norway on 9 April 1940 also confirms the importance of the plant.

Hakavik power plant

- Located at Eikeren in Øvre Eiker in Buskerud

- Built in 1922

- Consists of four generators, but only two are in operation today

- Produces "railway power"

- A new generator is planned in the old power plant

After major state investments in power development in Nore and Glomfjord, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) was established in 1921 to coordinate river system and electricity management and operate state-owned power plants.

The NVE building in 1921

In 1919, major construction work began in a mountain village in Nore and Uvdal Municipality in Buskerud County. Today, the Nore power plant stands as a monument to public hydropower development.

Nore 1 in all its glory. With its turrets, spire and arches, the power plant stands out in the landscape.

Magnificent natural scenery with waterfalls and shimmering mountain lakes were some of the features Nore could offer. The Numedalslågen River ran here, receiving its water from large parts of the Hardangervidda plateau. It was some of this water flow that would be harnessed to produce electricity for general use in Eastern Norway. Nore power plant – a cathedral of a facility in neoclassical style – was completed in 1927. In 1928 the first generators were put into operation.

Nore 1 became one of the first public power plants to supply electricity for general use to cities such as Tønsberg and Oslo.

When construction began, there were only a couple of small farms in Rødberg at the top of the Numedal valley. Today's town is the result of the development and operation of the power plant. The construction period was long, and in 1921 there were about 1 300 people working here. This occasionally led to major social problems during a time of economic hardship; for example the school yard was divided between the local children and the children of the construction workers. The influx of people also required construction of several temporary buildings, such as schools, homes, shops and a hospital.